From Kindle to Spotify, Hulu to iTunes, Netflix to Amazon, more consumers are purchasing goods online than ever before. Digital goods taxability is following suit. Whether or not to charge customers sales tax on these purchases is confusing in the extreme.

Traditionally, sales tax applied only to tangible personal property, but digital goods provide a puzzle that even the savviest tax managers have difficulty deciphering. The proliferation of virtual products and services has turned the already complex world of sales tax management into a thorn in the smartest tax manager’s side. The Census Bureau estimates that in the third quarter of 2014, online commerce totaled $71.9 billion — an increase of 2.5 percent from the second quarter of 2014. i The upward trend is projected to continue at a fast pace.

More states are attempting to require sellers to charge sales tax on digital goods to capture more revenue. As a result, businesses need to look closely at what they’re selling and the method of delivery.

The following discussion can help sellers determine whether or not they’re taxing digital goods in keeping with applicable statutes. The number of states taxing digitally or electronically transferred goods is expanding. Currently, approximately 25 states apply sales tax to digital books, downloaded music, and even ringtone.

While there has been some effort to streamline definitions of digital goods through organizations like the Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board and its 24 member states, much confusion still exists. Streamlined Sales Tax (SST) states are not required to adopt the SST definitions, but many choose to do so. Non-SST states may define digital goods through legislation, or the state department of revenue may adopt guidelines. The lack of uniform definitions makes tax compliance extremely difficult.

For the purpose of this discussion, digital goods are defined as:

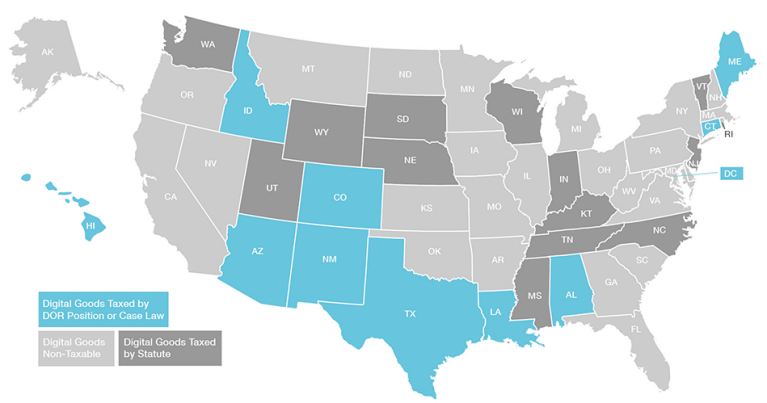

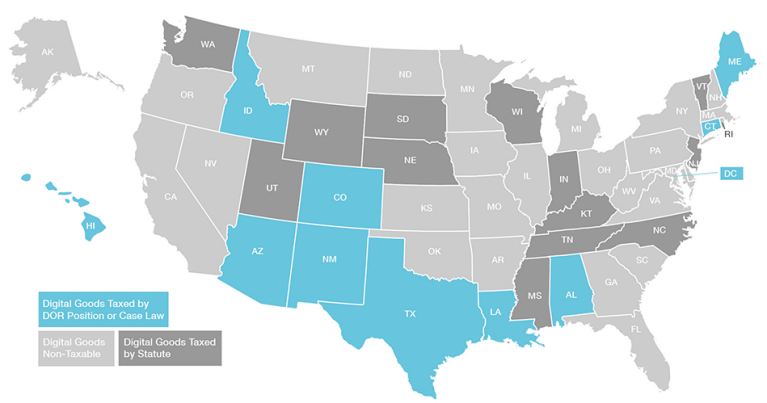

Roughly half of all states have passed legislation or follow regulatory rules that tax digital goods, while others have referred this authority to state revenue agencies. Even among Streamlined Sales Tax states, there is inconsistency in the taxation of digital goods; what is taxed in one state may be entirely different than what is taxed in another.

Downloaded music is one of the most commonly taxed digital goods. States that tax downloaded music also tend to tax ebooks. Taxing streaming video services is less common. The trouble with sales tax, as always, is mastering the exceptions in order to understand the rules. The taxability of tangible products is difficult enough without the added complexity of virtual or digital goods. For the most part, states play fast and loose with digital goods taxability.

States generally approach digital goods taxation in one of three ways:

1. Assume current tax law covers digital goods and handle issues on a case-by-case basis through General Interest Letters, etc.

Some states use their existing franchise, sales, and use taxes to tax purchases/uses/

transactions of Internet goods and services. States that do this include:

2. Define digital goods explicitly using either the Streamlined Sales Tax guidelines or another definition.

In addition to the 23 SST states, there are a handful of states that also define digital goods explicitly for purposes of taxability. States that take this approach include:

3. Define digital goods explicitly using either the Streamlined Sales Tax guidelines or another definition.

A handful of states currently exempt digital goods. This does not discharge seller responsibility, however. In the case of exempt products, there is sometimes a seller’s use tax or consumer use tax imposed. States that typically exempt digital goods from sales tax include:

For a summary of general state approaches to digital goods taxation, please see the following map:

The following three questions will help guide you in your efforts to decide whether to charge customers sales tax.

1. How do I know whether or not to charge my buyers sales tax on their digital goods?

Digital goods are generally taxed when:

As with all things sales tax compliance-related, it’s crucial to review the individual statutes in each state into which you sell.

2. Do I have digital goods-related nexus?

Nexus is the legal connection a state has with a vendor that gives the state the right to compel the vendor to collect sales taxes on behalf of the state.

Nexus analysis looks closely at a customer’s location, the location of an actual sale, delivery details, ownership elements, and the vendor’s location (including their servers or other technology). Determining nexus for sales of digital goods can be tricky given their nature, making compliance even more challenging.

3. How does “sourcing” affect digital goods taxation?

Sourcing means the location of a transaction and how it determines the applicable sales tax rules. For many states, the destination of the end user (the customer location) determines what sales tax rates and rules apply to the transaction. In others, the origin (seller location) of the sale is the determinant.

Digital goods sourcing also raises the question of whether or not the location of the buyer on a smartphone is the true “source” of the sales tax rules. Given the uneven participation in SST, and the diversity of related digital goods definitions and statutes, it’s easy to see why there is confusion among vendors.

While it’s unclear whether or not federal lawmakers will weigh in on the digital goods confusion, a bill was introduced in recent years that attempted to address the issue.

The Digital Goods and Services Tax Fairness Act attempted to require states to only charge sales tax on digital goods, only if same applied to tangible products. Though the bill ultimately failed, it did indicate one of the puzzles of digital goods taxability: inconsistent tax policy between states and potential unfairness resulting from it.

Whatever happens, it’s clear that states are turning to digital goods taxation to shore up revenue.

i Census Bureau, Quarterly Retail Ecommerce Sales, 2014